Infrastructure is so pervasive that earth system scientists and other researchers increasingly view it as comprising its own planetary subsystem: the technosphere. Given its ubiquity, it is perhaps unsurprising that research into various dimensions of infrastructure likewise abound. My work contributes to this scholarship by interrogating three inter-related infrastructural dynamics. Through policy and media analysis, household surveys, and semi-structured interviews with development practitioners, I examine the role of infrastructure in: mitigating and exacerbating environmental hazards, advancing colonial and neoliberal development, and state-making and regime maintenance.

Environmental hazards

Development

State building

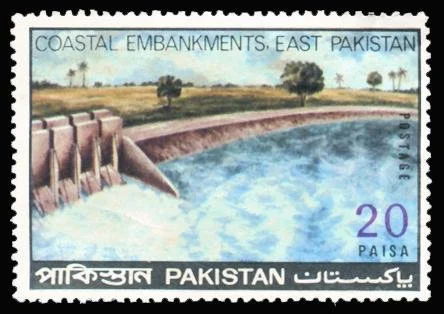

State planners and environmental consultants overwhelmingly advance infrastructural solutions to address floods, storm surge, seawater intrusion, coastal erosion, and other water-related hazards. However, embankments, sea walls, sluice gates, and other so-called ‘hard measures’ often fail to mitigate environmental hazards, make them worse, or even introduce new hazards (Climate and Development 2020). Infrastructural violence emerges not just in moments of construction, failure, or decay but also when systems function as intended. Such impacts arise from the social, spatial, and temporal exclusions that place harms beyond the purview of a given project (Geographies of Slow Violence 2021).

Infrastructure is a central pillar of development agendas to improve human health and well-being through, for example, the provision of water and sanitation, electricity, and access to information. The Sustainable Development Goals are the hallmark of such activities. However, infrastructures are also vital to [settler-]colonial and capitalist ambitions for claiming and transforming land. In India, the Farakka Barrage began as a colonial proposal to facilitate commerce through Calcutta (Water International 2017), while the International Dam in the US-Canada Boundary Waters enables the flourishing of European-descended settlers at the expense of the Anishinaabe (Water Alternatives 2021, Environmental Management 2025). Meanwhile, in Vietnam (Development and Change 2023) and Bangladesh (Annals of the AAG 2020), embankments alter agrarian landscapes in favor of export commodity production that exacerbates precarity for the most vulnerable households.

Although the state and capital are mutually constitutive, the state leverages infrastructure in distinct ways from that of capital. My work shows how states enact border security measures along landscape features like international rivers to assert territorial claims and police cross-border movements. In such cases, transboundary rivers themselves serve as border infrastructure (Political Geography 2021). Border walls and fences not only shore up defenses where inhospitable borderland environments fail (Political Geography 2021), but their impacts on wildlife habitat and migration are summarily dismissed by national security mandates (Undisciplined Environments 2021). Flood control infrastructure, like embankments, also undergird state legitimacy. However, such conspicuous displays of environmental regulation can obscure underlying drivers of hazards, thus perpetuating their harms (Annals of the AAG 2020, Climate and Development 2020).

Together, this work recognizes that infrastructures produce and are produced by particular social orders while denying others. How, then, might we envision and co-create systems that support collective flourishing?

visiting a sluice gate in an giang province, Vietnam

farakka barrage diverts dry season water flows away from bangladesh toward west bengal (india).

1971 stamp from then east pakistan (now bangladesh) features coastal embankments introduced to control floods.